Melanie Schoeniger

I am thrilled to finally bring you the images and words of Melanie Schoeniger, for this has been a long time coming. Her work is shaped not by shortcuts or spectacle, but by years of steady commitment to seeing, making, and staying with the process. Her photographs feel earned. They carry the weight of time spent learning the language of materials and embracing uncertainty.

Her journey as a photographer is one quite rooted in perseverance. There is a willingness to keep showing up, to trust intuition while refining craft, and to allow both mistakes and successes to inform what comes next. Never one to chase trends, she has built a practice grounded in patience and intention, where dedication becomes part of the image itself.

I’ve tracked Melanie’s work for a few years now, and in this interview, we explore not simply the photographs but the discipline that sustains her creative life and the quiet determination that continues to shape her vision. As someone who is constantly testing the waters and learning about herself as the images move her forward, she is one to watch and learn from as well. My sincere thanks to Melanie for the time and attention it took for this interview.

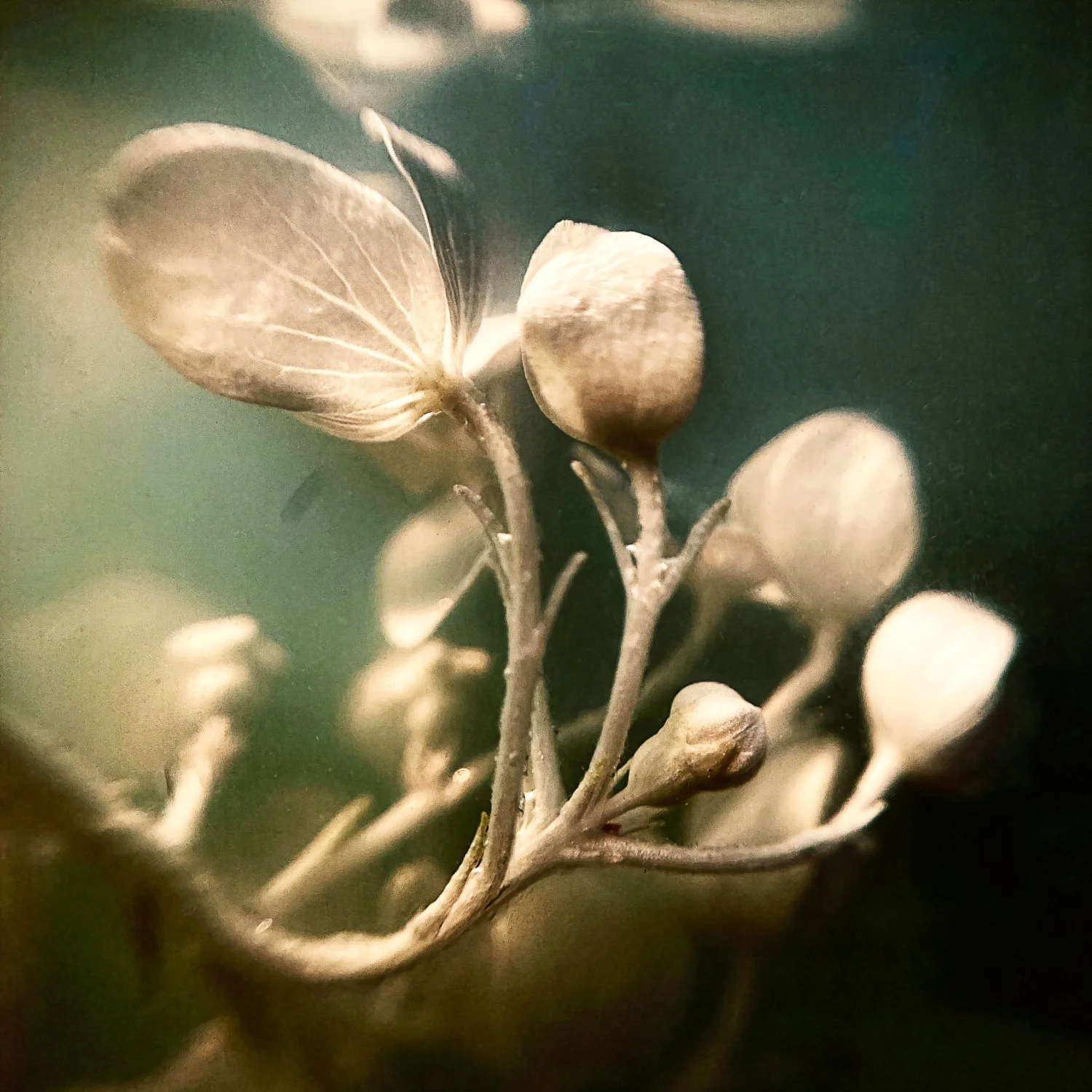

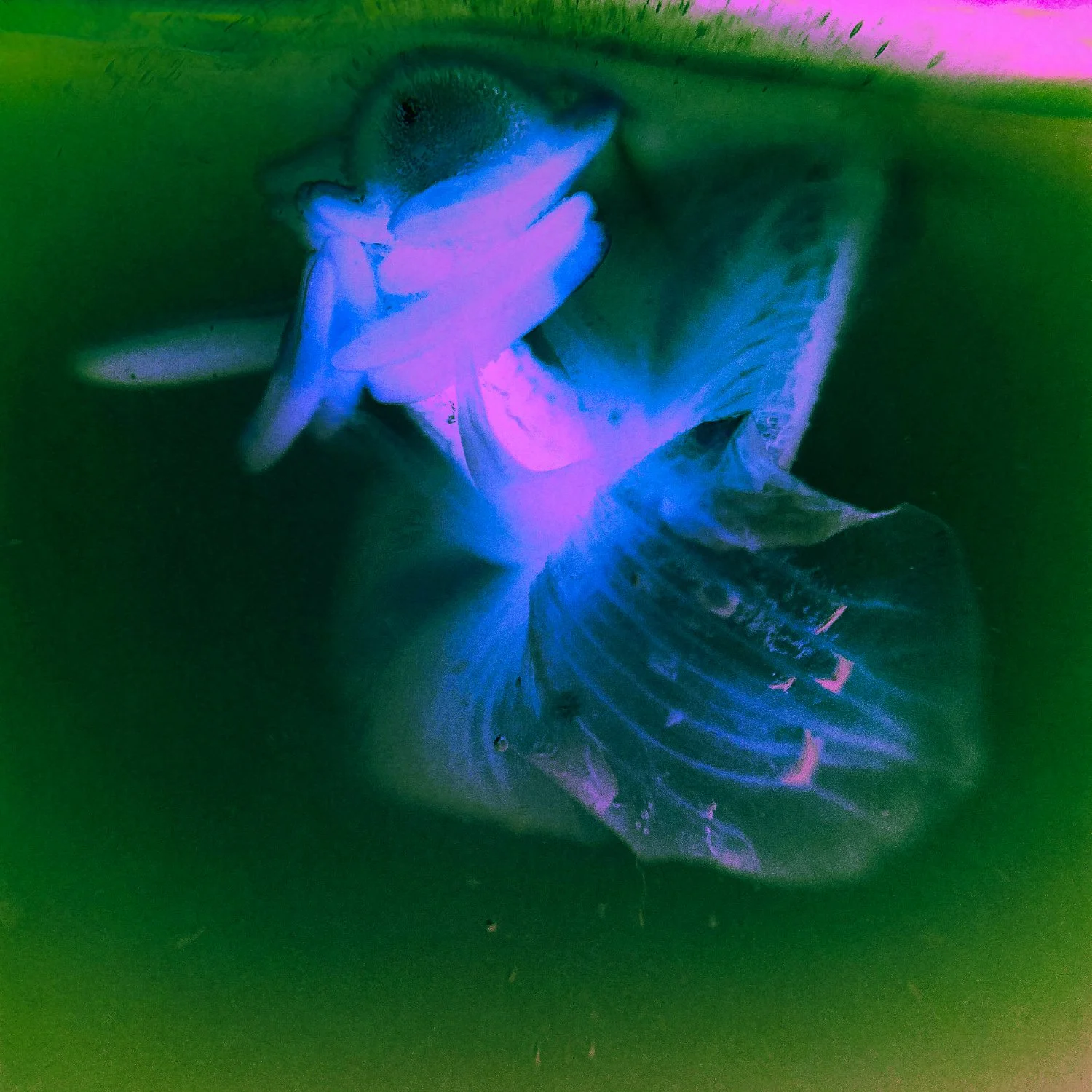

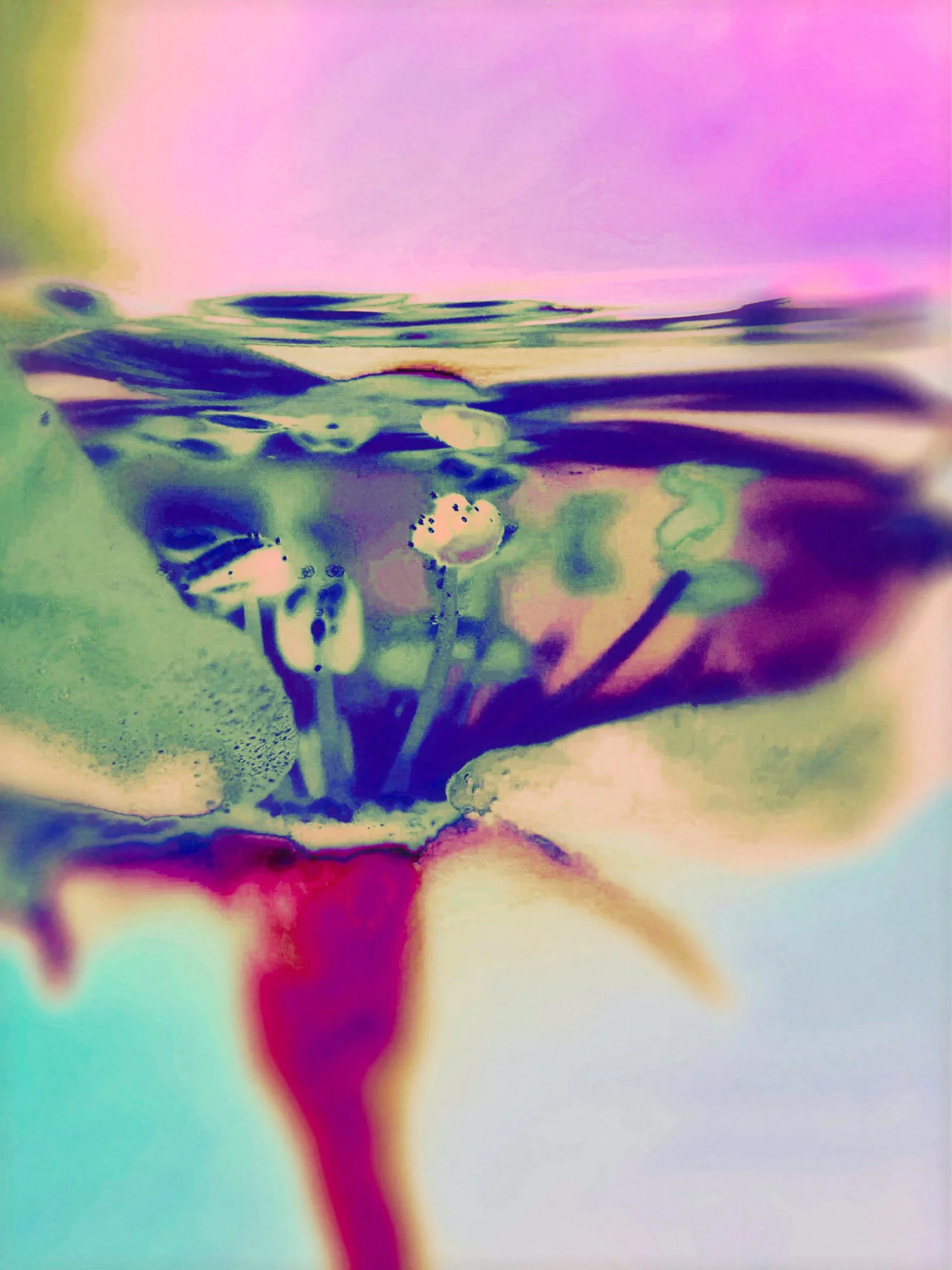

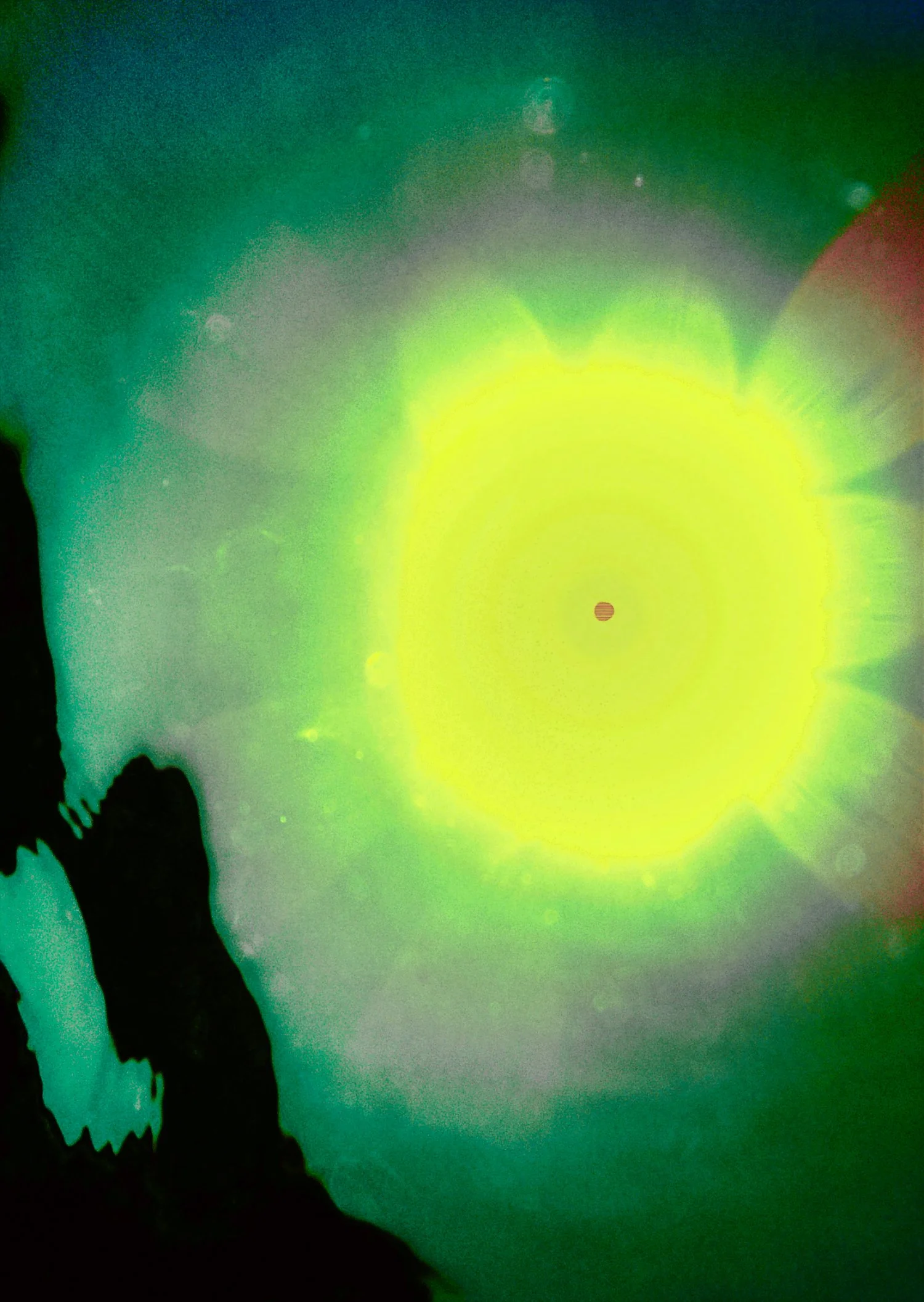

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

Bio -

Unpacking the wonder of being alive, Melanie Schoeniger explores themes such as perception and interconnectedness and contemplates our place in the larger scheme of things. The German artist uses a philosophical yet intuitive approach to reveal the beauty and essence of nature as a means to create awe and wonder and to uncover mysteries beyond all stardust.

To honor a sustainable process, Melanie experiments with alternative printing techniques and materials; she also creates handmade artist books. She perceives all her work as fundamentally being climate work, contributing to a life-sustaining future.*

Her award-winning work has been published and on view internationally.

*She is a member of Eco Echo Art Collective

Interview -

Michael Kirchoff: Thanks for participating in this interview, Melanie. I'd like to start with your start in the visual arts. Do you have any recollection of your first introduction to cameras and photographs? Was your interest in them immediate, or did it take multiple reminders of image-making to reel you in?

Melanie Schoeniger: I really appreciate your invitation to Catalyst: Interviews. Heartfelt thanks for having me!

In my childhood, of course, there were family pictures taken and glued into albums. And around the age of 8 in the early 80s, I remember vividly our family trip to the U.S. to meet relatives in New York and Washington, DC. My father took a huge number of images on DIA slides, and we would watch and show them on a slide projector over and over again.

(Later, during my studies, I would use this projector to project my photos onto canvases to paint with oil paint.)

Photography appeared to me like a technical opportunity to document and capture moments in time. And the idea of sheer representation did not allure me at all to step in and create.

In my teenage years, my music teacher offered a photography class in the afternoon, teaching the basics with an analog reflex camera. Then I started playing and taking pictures in old cemeteries, similar to your amazing images, which I know you captured during your travels in Europe. All in black and white. And, serendipitously, a friend of my father, a professional photographer who wanted to renew his darkroom, gifted me his old equipment. Suddenly, I had a darkroom installed in my grandmother's house, in a small room where she kept her perennials during the cold season.

Then I got hooked. Immersing myself in the playful flow of experimentation and creation, and in the infinite possibilities of artistic expression, there - dodging and burning, multiple exposures, painting on developer partially, solarization, photograms with my grandmother's plants, etc. Savoring this magical moment when the image reveals itself and comes into being, when vision and reality merge (in an anticipated way or not) - this is what, still, every time anew, makes my heart beat in the thrill of anticipation. Also, the hands-on process of literally manifesting a piece in space and time with steps and variables, the more complex the more unique, and the challenge is what I love. The childlike feeling of messing with water, too. And the idea that light and water, these elemental forces, are in a kind of playful dialogue with my intuition.

Later in my life, after my grandmother had died, I had to let go of my darkroom, and a new door opened. Non-toxic alternative processes like cyanotype enabled me to create more easily and sustainably. Also, back then, with little children around, without a darkroom, I exposed on my terrace and coated and rinsed on my washing machine. Rekindling and uplifting my creative process, adding an even more meditative aspect in terms of time and maybe complexity.

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

MK: Can you describe a time when nature presented you with something that felt like a personal message—something ephemeral or hidden—that shaped a body of work or even changed your perspective?

MS: In my 20s, as soon as I knew I would travel to Australia, I took diving lessons in the Olympic swimming pool in Munich to be able to dive at the Great Barrier Reef. (Growing up far from the sea, interestingly enough, I had this fascination for underwater life and collected photo books on this topic; I even had painted my bathroom in an underwater scene).

And on my first dive in this coral reef, that was it for me. Later, I dived with and underneath Manta Rays, what a divine, literally breathtaking encounter.

Such a different embodied experience of mind-blowing beauty, being immersed in a whole new, immense universe with altered senses, weightlessly connected, has left a huge imprint on me.

I turned this deep love and later almost unbearable grief into agency with my series Octopus Garden and beyond the edge of darkness. (And I think maybe there is still more to evolve.)

On Octopus Garden: During Covid and entangled in climate grief, I realized, heartbroken, that coral reefs are on the verge of extinction, that they might vanish in my lifetime and my kids and the next generations will not be able to witness this incredible wonder of biodiversity and amazing beauty. Not to mention its importance for our planetary health and all the more-than-human beings living in and depending on it.

I played with my homegrown plants, submerged them in a vase in my kitchen, and captured them with a macro lens on my iPhone. Watching their metamorphosis, I started dreaming of a life-sustaining future, imagining that plants contribute to a new form of underwater life.

Later, another series evolved. Called beyond the edge of darkness, inspired by the book of marine biologist Dr. Edith Widder about the deep sea. With this series, I widened my horizon not only into the spacious volume of the vast sea, highlighting bioluminescence and surreal colors inspired by coral reefs and nudibranchs, and envisioning how underwater species sense the world via ultraviolet and infrared sight (Imagine the oceans' volume in comparison with the surface we live on, and all the undiscovered species! And to refer to your question again: it is both ephemeral and hidden from daily human sight and consciousness, but also in terms of my personal creative approach and process. I would love to mention and thank Susan Burnstine here. I developed this series during her class.

MK: Your use of alternative photographic and printing techniques often adds a layer of unpredictability to the work. How do you decide when to surrender to process and when to assert control over it?

MS: Love that you mention unpredictability, it is super important for me. I think of it as a kind of freedom and openness, a door towards the field of possibilities; as something inherent in how nature evolves and emerges (think of the cells in a caterpillar turning into a moth, incredibly mind-boggling) It reflects my way of working with the flow, my intuition, the materials; my process always feels like a dialogue or a dance. It enables co-creation, and something unique arises that cannot be reproduced exactly in this way again. (Without it, it would be just a linear, limited, foreseeable machine-like operation).

In practice, I trust my intuition. Also, it depends on whether I am honing my skills and might ruin a piece to get the answer to a question that appears, like what happens if I add/do this and that. Those are stepping stones for future paths I might not have taken without risking, so I cherish them, too. And try to start again with my new knowledge, which might take some time and patience, and I will enjoy it along the way. Always trying to keep a beginner's mindset, approach it with a fresh perspective, and avoid the perfectionistic trap.

MK: How does your intuition guide your technical decisions, such as camera format, lens, exposure, or printing method, especially when working with nature as your subject?

MS: The older I get, the more I realize my intuition is my most important ally.

Sometimes I find myself stuck or wrestling with minor details, my mind entangled. But contemplating the big decisions that you mentioned above, I realize that they mostly unfold naturally - seemingly without using my thinking mind - as part of my process of playful curiosity guided by intuition. And if there is anything in question, I create, compare, and then kind of feel and know which direction to go in. If not, I put it down and let it incubate, dwell, and grow in the vast realm and fertile soil of my unconsciousness.

I imagine that my intuition works with my unconsciousness, drawing on my cornucopia of stored experiences to guide me. My ideas and contemplation mostly inform my choices; my art seems to be a way of detangling my thoughts, digesting them, transferring them into symbolic experiences in an immediate way, records of my reflection of being in the world (and its meaning), my kind of mythopoetic apprehension of life (as Glen Slater calls it).

The printing method defines the final manifestation, mood, and appearance, and is very important to me. For example, I might test a motif as cyanotype, but Riso printing or photopolymer gravure might fit better. Of course, the paper or substrate makes a huge difference. (I am in love with the materiality of Japanese and matte papers, vellum, wood, and metals; resonating with the book In Praise of Shadows).

And as for nature, I cannot think of any other subject. (Actually, if you consider it in the broader perspective, there is nothing that is not nature or interconnected with it). What I also love about nature as a subject is that it is not fixed, but flexible, animate, and changing. Actually, for me, it is the symbol par excellence for the wonder of life itself. It naturally reflects perennial questions; it is the source of everything and anything, literally and poetically.

MK: You seem to approach your subjects with reverence, as though each leaf, wave, or cloud is a sacred form. Do you see your work as a kind of quiet ritual or offering?

MS: Definitely! I love that you bring this up. I see my artistic practice as a kind of spiritual praxis, my way of connecting to the ground of being, a reciprocal act of love, care, and kinship contemplating the wonder of existence.

For me, everything is interconnected, and everything is sacred. We are the universe experiencing itself.

William Blake put it so beautifully: "To see a world in a grain of sand, a heaven in a wildflower, hold infinity in the palm of your hand and eternity in an hour.”

Art pulls our perception towards the soulful and enchanted, occasioning reverence and awe and encouraging extended contemplation. A sense of the sacred arises through the careful attending of inner and outer nature. Restoring an animated presence, it tends us toward the embrace of this world.

All my images are tributes, metaphors of belonging, archetypes carrying embodied implicit energy. I am deeply influenced by Buddhist ideas and consider it part of my purpose to spread inspiration and joy and to contribute to a life-inducing future. Reversing the pattern of manipulation and exploitation and tending a worldview of co-creation that involves agency, humbleness, and responsibility.

The underlying current of all my work is the notion that we have to rethink the story of who we are and how we relate to the planet.

MK: Your work often evokes the passage of time, not through narrative but through texture and form. How do you approach time as a visual and philosophical element in your work?

MS: Another wonderful observation! I contemplate the different dimensions of time. Akin to macro and micro cosmos, depending on scale (I am intrigued by macro lenses, microscopes, and the Hubble telescope), time for me behaves similarly. There is the deep time of a mountain that is only a slow wave (love that title of Judith Stenneken) or more uncanny like nuclear waste.

There is another time, like Carl Sagan stated: “We are like butterflies that flutter for a day and think it is forever.”

I think about non-linear time. I think about Kairos and the quality of time—the incredible feeling of timelessness of being in the flow. And I often contemplate future beings and our relationship to them, being their ancestors. What we decide and do now shapes their being, even their coming into being at all. In addition, if you consider light as a co-creator in photography itself, as carrying not only energy, but also stored time. (It takes about 8 minutes for a sun ray to reach the earth, not to mention starlight!) And a print then might carry all the time stored within its elements (the life of a tree, the water that might have been part not only of oceans or clouds but also of other beings, like the carbon and other elements, too), as well as the history of its emergence through my artistic process that might include various layers of time itself.

MK: Many of your images evoke wonder more than explanation. Do you see your work as an invitation to mystery rather than a statement of truth?

MS: 100%. Awe, inspiration, and wonder are my main aspirations. I am not interested in a statement of truth in a kind of documentary or representational approach. What's more, big truths seem to be unfathomable and can only be expressed through metaphor. It's these kinds of truths I am interested in, and they are implicitly interwoven into my art.

For me, mystery has an inherent capacity to point towards these truths in a vague, elusive way. And importantly, to open up a space for, and in the perceiver, to interact, as truth is a kind of experience, something that needs to be felt, and only then can it be known.

As we witness, unfortunately, with multiple crises such as biodiversity loss, showing documentary, fact-based kinds of truths seems not to be enough to touch people's hearts in terms of change of behavior and mindset. In this way, I truly consider my art as activism, especially when it comes to intentions, hoping to bridge the almost unbearable cognitive dissonance.

If my art in any way can work as a spark of imagination, I am more than happy. I like to think of the butterfly effect here. At the same time, trying not to aspire for the outcome, I would do it anyway for the love of the process and my own sanity, I just follow my bliss.

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

MK: How do alternative processes, like cyanotype or hand-coated emulsions, help you create not just an image, but a sensory experience?

MS: My handmade print is the result and subject of my poetic discourse, the syntax of my multi-layered process using photography in all its alchemistic ways as my artistic language. It is animated during my process to the extent that we liken it to an organism; it carries and stores history, memory, thoughts, and energy. (I was so touched when a reviewer of my handmade artist photo book, who did not know me at all, wrote about my work, referring to all the ideas I contemplated during the creation and about key attributes of my personality.) It has many levels, and like a haiku, its essence is not to be found literally but between the lines.

Metaphors enable us to find the universal in and through the unique. The nature of this art form is to create unique results, making it a perfect match. Every step makes it even more unique - but only applied if “necessary."

In terms of sensory experience, I think that we are limited by our senses, and there are so many more layers to reality that we cannot perceive or even imagine. And that there are layers we can only perceive unconsciously. These are the ones I love to speak to. So if you think about a photo on a screen, a flat “representation" of reality as opposed to a handmade print, we then enter into the embodied “presencing" realm of life and three-dimensional space with something you are also able to touch, hold, and even turn - then you would see all my rudimentary notes! - and interact with it. You might even smell it. The paper, the coffee from toning or thinking about whether the pigment has its own scent. Similar to how you might approach a blossom, where you do not know if it smells (at least for you) or not. You will see the paper quality is altered and in parts condensed and uneven due to the many times of rinsing, drying, and shrinking. So it seems to me that it has an inherent multiplied capacity to interact, to spark imagination, and enter a relationship that then includes the perceiver as well. Like with metaphors, this is a bi-directional state of affairs. Or think of Indra's net.

I also like the idea of translating and implementing my vision of a life-sustaining future that we might call a "Symbiocene," replacing the “Anthropocene." Creating a future I want to see in my process and experimenting with options and opportunities. For example, I try to create in a vegan, plastic-free way.

So I leave plastic aside and use vellum for my negatives, printed with my refillable eco-inkjet printer. I do not use gelatin. And experimented with agar-agar derived from algae. I do not use PVA sizing, but I do use none (or starch). I do not use Bichromate (which is also banned within the EU due to toxicity), but I am testing Diazo Gum and Lupin printing. If I tone, I re-infuse my French press morning coffee. But that does not mean in a Kantian kind of way that this is imperative neither for me nor for others. It is a playful challenge born out of curiosity to gain knowledge.

MK: You often speak of photography as a way to reveal the “essence” of nature. What does that essence feel like to you when you're in the act of making an image, before the photograph even exists?

MS: It feels like a vibrant spark, an alluring call to attention, like an invitation. It kind of changes the vibrancy around me, even the flow of time, at least in my perception. And it is not only present and interacting before or while I might make an image in terms of taking a picture, but it is there all along the process eg while looking for the part of the capture that I will crop, deciding what it needs to be revealed in little steps like gradient curves or creating digital negatives, or asking me what's next in terms of toning or layers in my analog alternative process. The essence is something that is always there, an inherent quality – irreducible, primordial, and unfathomable; at least with rational and conscious means. It can only be approached in poetical and symbolic ways. (Think of "the finger pointing to the moon")

Joseph Campbell called it the divine radiance behind all things. It might be something like the creative spark that animates the world, the elan vital—the “nothingness" in a Zen context, or the possibilities from a quantum mechanics perspective. And Rilke and Jung referred to it as a kind of center of a spiral, where we circle around and towards it.

MK: Do you collaborate with like-minded individuals on projects, or do you find it more productive to handle everything yourself? Are there any collaborations in the past that have been particularly beneficial?

MS: I kind of strive towards autonomy. I realized I want to be as flexible as possible and be in charge of all decisions, not having to compromise (which I often had to when I worked for clients in my former career as a creative director). This seems to be a kind of protective mode to stay true to my art and its unfolding, a bit like a mother taking care. This is also the reason why I self-published my first artist book: It was part of my aspiration for this project to create it as sustainably as possible, questioning every step along the way, and realizing it completely by hand.

That said, in a bigger scheme, I do love to collaborate. E.g., for some specific realizations, I enjoy getting on board with masters in their field: Drucken3000 in Berlin for my Riso printing, Eric Levert for Photopolymer Printing, Viktor Kostenko for framing.

Connection with like-minded spirits is crucial to me. I am so grateful to have found friends around the globe who approach life in a creative way that I can exchange with about everything I resonate with, from photography to books, plants, and more.

Furthermore, I am so happy to be part of the Eco Echo Art Collective that my talented photographer friend Sarah Knobel started. (Our friendship started when she interviewed me for my series To Paradise for LENSCRATCH) We regularly meet online, and we edited a group show around the theme of "our place in the scheme of things, "inspired by my favorite part of Mary Oliver's poem Wild Geese. It has been on view already at St. Lawrence University, NY, and will be shown in Quito/Ecuador and in Middlebury/U.S. next year.

MK: Do you find that certain images work better in an exhibition vs. a book project or even in an online capacity? Do you ever leave any out because you feel they might not be as strong in one venue compared to another?

MS: Yes, I do think the appearance of images and their perception highly depend on their manifestations, state of display, and context.

A wonderful enlarged scan of a Cyanotype on Kozo paper that reveals its beautiful structure in a poetic way might look amazing on a screen, but to transfer this into an inkjet print that still conveys a similar mood might not be as easy. On the other hand, there might be a gorgeous print on metal or a silvered cyanotype that is beautiful in reality, but so hard to capture and almost unable to transfer to the digital realm in an apt way. In a sequence of images for a book, I might (and did) use images that add to the experience of the book and its rhythm, even though I do not consider them as really strong or essential to be part of a condensed digital essence of the body of work itself. Or a strong image might not be part of the book as it doesn't fit the bigger flow somehow, and you need to leave it out. For exhibitions, there is way more to think of and feel in terms of space. I kind of like to envision it as a 3-dimensional musical piece. There are different threads and instruments that need to resonate and reverberate harmoniously. From the manifestation of the image (print, framing, etc), the space and light, the color of the wall, the installation in terms of proportions and interplay, you hear me.

Currently, I am working on an exhibition proposal for Oceanic Feeling with Ilias Georgiadis, and I find it very alluring to be able to play with scale, depth, and materiality.

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

From the collection, Oceanic Feeling

MK: Speaking of books, I know you are working on a couple of different iterations of projects in book form. What has that process been like for you?

MS: My first handmade artist photo book, To Paradise, has been an amazing deep dive full of joy and learning.

Looking back, I would not want to change anything, but at the same time, I am happy I did not know the amount of work and challenges I would encounter on the way when committing myself to it in the beginning.

Also, I still like the idea that I decided to work on it only if it gives me joy, not to force it. In reality, that meant I would put the project down for 3 months, as I did not feel ready and intrigued to work on transferring my images into a kind of digital negatives for Riso Printing. I really love sequencing images, and I think I've gained a better understanding of this kind of flow and rhythm, e.g., in blank pages and the space around the image within the object.

In addition, handcrafting my book, coptic stitching as a meditative act, reminded me of times spent with my grandmother knitting and crafting, and rekindled my love for working with thread.

This year, I have been working on my new series, Oceanic Feeling, and crafted a book dummy during my amazing Masterclass at Origini Edizioni in Italy in May. I so enjoyed it and my understanding of the book as an object has grown exponentially thanks to Ilias Georgiadis, Mathilde Vittoria Laricchia, and Eugenia Koval.

MK: If photography is often thought of as a way to document or preserve, what does it mean to you to make work that seems to dissolve boundaries—between inner and outer, material and spiritual, known and unknown?

MS: Photography - in a wider sense as painting with light - is what I am drawn to. It enables me to express myself in many ways. (There is such an immensity of possibilities, combinations, and applications that often flash through my mind). It is a kind of language that evolved in and with me over time and is ever-evolving with every project and every new skill. (And like every language, it also contains history.)

Back to your question, in my mind, these boundaries you mention do not exist (they exist only as concepts in our perception of reality). Maybe they are like cell membranes open for osmosis. Photography is my vehicle to bridge the gaps between these boundaries you mentioned and explore the vast field in-between their poles: Parts of my inner realm can be transformed, rendered and manifested into the outer realm, my process could be described as applied materialized spirituality and as I mentioned above: I love to wander the shorelines of ignorance hence expanding both, my knowledge and my not-knowing. The dissolution, integration, and synthesis of opposites seem to be an underlying thread, reflecting themes such as individuation, growth, the human condition, and the wonder of existence itself.

MK: Thank you again for your time, Melanie. Is there anything else you'd like the reader to know about you or the photographs you create? Or maybe there is a project coming up that you'd like to hint at a little more?

MS: It has been my pleasure, Michael. I am beyond grateful for your support and all your efforts! Oh, and there are various projects. First of all, I will relocate with my family to Berlin next year. That will take some time and energy. And I am so excited! Artistically, I have already created a book dummy of an Oceanic Feeling; we will see where this leads. Currently, it is on hold and incubating. But I am working on the final development of this series, including exhibition plans.

Also, it seems like I will pick up Octopus Garden and beyond the edge of darkness again for an inspiring book collaboration that I want to focus on once we are relocated. I would also like a third chapter, I want to unfold on this underwater topic.

Besides that, I am experimenting a lot to add color in a non-toxic way to my alternative processes. As I am not satisfied with cyanotype toning opportunities alone and want to use pigments, I play with Lupin and Diazo Gum printing. Maybe a series is unfolding once I have honed my skills enough. (Thanks to Anne Eder, I am part of a research group that exchanges knowledge on this topic.)

Then there is a vast archive of ideas just waiting to have a turn. Maybe I will teach again or write some articles, too. And I am eager to immerse myself in the creative community in Berlin.

You can find more of Melanie’s work on her website here.

All photographs, ©Melanie Schoeniger